“The Green Room” series on pipelines continues. In the previous three segments we discovered the web of underground infrastructure is more complex and extensive than most realize. And, while pipelines are safer than other forms of energy transport, threats to water are high on the list of concerns. Where are the pipeline policy decisions being made? In this segment, we look for “the deciders.”

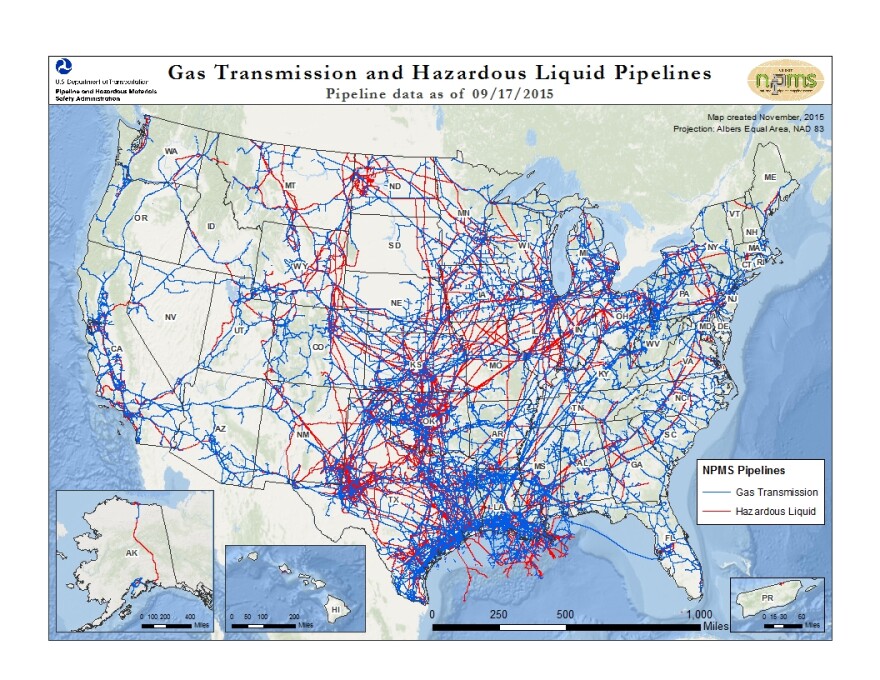

David Fair: This is 89-1 WEMU and I’m David Fair. Welcome to this month’s edition of “The Green Room" and part four of our series on pipelines. Pipelines are approved, sited and overseen by a combination of agencies. It depends on a myriad of factors including size, whether they’re in-state or interstate and gas or oil. Some area residents and members of local government welcome new pipelines as the safest form of transport for an energy that feeds our way of life. Others have serious concerns. Do locals actually have a say in the matter? Barbara Lucas stepped back into “The Green Room” in search of answer to that question.

Owls calling.

BL: Hiking through woods in western Washtenaw County, we encounter Barred owls, next to an open area. Signs say, “Warning: Petroleum Pipeline.” A wide, freshly mown swath snakes off into the distance. It’s right next to the Rouge River. A spill here could quickly travel downstream. Curious, I call the number posted. I’m told it’s an old pipeline, and would likely not be approved in that location today.

Fade out natural sounds.

BL: What about now—do local communities have much influence over pipelines being built in their area? The new Nexus and Rover gas pipelines were recently run through Washtenaw County. Apparently, getting local concerns addressed can be a challenge.

Evan Pratt: We went through representative Debbie Dingell's office to get a contact at FERC.

BL: That’s Evan Pratt, Washtenaw County’s Water Resources Commissioner. The FERC he’s referring to is the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Its five members, appointed by the U.S. president, approve interstate gas pipelines.

Pratt: But they really didn't respond when we said, we've got this specific issue, can you help get this resolved.

BL: He says they also contacted PHMSA, the federal Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

Pratt: …due to our concerns about the location and the number of people who would be impacted if there was an issue.

Crowd chanting: Back it up! Back it up!

BL: That’s a July 2017 protest against the Rover pipeline, near the YMCA’s “Camp Birkett,” at Silver Lake in Dexter Township. According to the Washtenaw County Board of Commissioners, the pipeline route cuts off evacuation for potentially thousands of people. That board and four other local governmental bodies passed resolutions against it.

Fade out sounds of protest.

BL: Ultimately, the pipeline thickness and the number of valves were increased. But the federal government did not reroute the pipeline.

Sounds of pipeline construction.

BL: Evan Pratt says that while they can’t dictate routes, local governments do have the authority to “permit” pipelines near rivers and drains to ensure they’re constructed safely. But local oversight is not always warmly received.

Pratt: It's really on us to watch what's going on and to chase the pipeline companies long enough until they agree that they're required to get a permit from our agencies and, believe me, they tried to demonstrate they didn't need to get permits because they saw it as an obstacle.

BL: And he says the guidelines provided by local government are not always followed. Redoes must sometimes be forced, such as when…

Pratt: It seems that the contractor either was never provided with all the detailed drawings that we required when we permit it with a gas company or the contractor was provided the drawings and promptly stuffed them behind the seat of their truck or something.

BL: There is one community in the U.S. that wielded a lot of influence on a pipeline installed in their area: Austin, Texas now has what’s been called the safest pipeline in the country.

Carl Weimer: It has an external leak detection system that can identify leaks on that pipeline at much smaller levels than what the federal regulations require.

BL: Carl Weimer is executive director of the non-profit, national Pipeline Safety Trust. He says when a pipeline was proposed over their precious aquifer, Austin sued the company, and won a settlement. In addition to the extra-sensitive leak detection, they insisted on…

Carl Weimer: …daily patrols of the pipeline that goes across the aquifer and they put a cement cap over the top of that pipeline to make sure that people working in the area would like backhoes are putting in fencepost and those types of things will get the cement instead of the pipeline and not cause a spill that way.

BL: What about in Washtenaw County? For instance, the Nexus company assures me their pipeline meets or exceeds federal regulations. But their patrols are weekly not daily and there’re no cement caps. The inspection PIGs that look for weaknesses are sent inside pipelines only once every seven years, the federal minimum. Weimer points out...

Weimer: People can agree to whatever they want to in a settlement, and the pipeline company agreed to do better leak detection and more inspections. It's not that they passed a law to require that.

BL: While locals can’t pass laws regarding pipeline routes or safety, they can alert the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality to potential environmental threats. But new legislation signed into law by Governor Snyder, sets up private-sector-based panels to oversee the decisions made by the DEQ. Here’s Mike Shriberg, of the National Wildlife Federation.

Mike Shriberg: What it does is it puts an unelected body in charge of oversight of our environmental laws and not only an unelected body but one that actually heavily draws from special interests. You'd have the oil and gas industry represented you have the utilities represented,

BL: Shriberg says he has no problem with their weighing in. But…

Shriberg: The problem with this is it actually allows him to overrule the people whose job it is to actually enforce our environmental laws.

BL: Supporters of the panels feel they’re necessary to prevent what they call arbitrary decisions by the DEQ that prioritize the environment over other concerns. Here’s Republican State Senator Rick Jones:

Senator Rick Jones: There have been cases in the past were the DEQ wasn't reasonable at all.

BL: The example he gives me is from Charlotte, Michigan, where the DEQ wanted to fine a city cemetery that had drained a wetland.

Senator Rick Jones: But again this was an existing drain and they were essentially cleaning it out. I think the DEQ overstepped in that case. So we do have to have someone watch the DEQ to make sure that they are reasonable.

BL: DTE spokesperson Peter Ternes tells me the new panels will simply be a continuation of current collaborative efforts, and public input opportunities will continue to abound. When asked if environmentalists will have less say, he says…

Peter Ternes: There are plenty of opportunities for input in the MPSC process and the MDEQ process.

BL: MPSC stands for the Michigan Public Service Commission, which approves gas pipelines within Michigan and oil pipelines both in state and crossing our borders. How much weight is given to the public input they receive? Here’s J.C. Kibbey of the Union of Concerned Scientists.

J.C. Kibbey: There were 10,000 people around the state who signed onto a petition encouraging the Public Service Commission to send DTE back to the drawing board for an expensive gas plant and to take another look at the clean energy alternatives.

BL: He’s referring to DTE’s nearly billion dollar St. Clair County gas plant proposal, which will connect with some of Washtenaw County’s pipelines. The Michigan Public Service Commission approved it in April. The Commission has only has three members, all appointed by Michigan’s governor.

Kibbey: So the new governor, whomever it is, is going to appoint, at the very least, one to potentially all three members of the Public Service Commission and that's going to have a big impact and a long lasting impact on Michigan's energy future. That’s because next year, in 2019, DTE is going to submit its plan for the next 20 years in terms of where it's going to get its power what kinds of things they are going to build.

BL: In an April statement announcing their approval, the MPSC said the plant is necessary to allow DTE to retire coal plants. Here’s Matt Wagner, manager of renewable energy development at DTE.

DTE: In 2017, CEO Jerry Anderson announced a reduction in carbon emissions of about 80 percent by 2050. Eventually we'd like to be all natural gas and renewable energy or clean energy sources. That is in large part because, by 2040, we will likely have all our coal plants closed.

BL: And retiring coal is a huge victory for the environment, both local, and global. Once again, there’re multiple ways to look at the proliferation of fossil fuel infrastructure. But one thing’s clear: it’s not locals who make the big decisions about pipelines. It’s higher authorities, who are appointed by the people we elect.

Construction sounds.

BL: In “The Green Room,” I’m Barbara Lucas, 89 One, WEMU News.

David Fair: Despite concerns, pipelines are often approved because they’re deemed beneficial for the public good. What is the public good? Next month, the last in our Green Room series on pipelines will look at the big picture. To hear the previous reports in “The Green Room” series on pipelines, visit our website and archive at WEMU-dot-org. This is 89-1 WEMU-FM and WEMU H-D One Ypsilanti.

Resources:

Federal Energy Regulatory Commission

Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration

Michigan Public Service Commission

Press release: MPSC approves DTE's St. Clair County natural gas plant proposal, April 27, 2018.

Can Michigan's polluters be trusted to self-regulate? Detroit Free Press, Dec. 18, 2017.

Non-commercial, fact based reporting is made possible by your financial support. Make your donation to WEMU today to keep your community NPR station thriving.